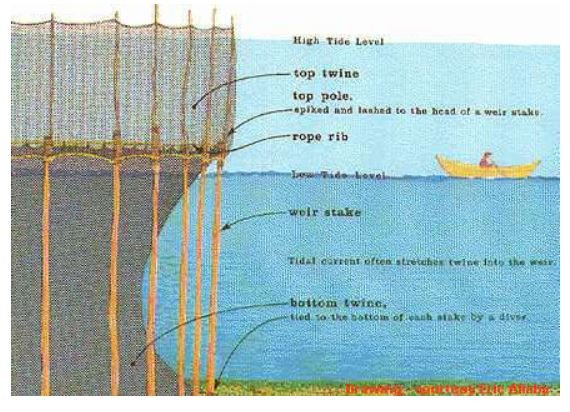

Illustration by Eric Allaby of a herring weir from his book Grand Manan.

For over a year before the start of this photography trip, I’d been reading about, and become fascinated with, herring weirs. Despite the fact that weir fishing is dying out in many parts of the world, there is a living weir fishing culture in the Bay of Fundy in Canada. Weir fishing is a very old method of fishing - the stakes of an ancient fishing weir have been found near to the Bay of Fundy, in Maine, dating back over 5,000 years - and it has been practiced around the world in almost all seaside and riverine cultures going back millennia. Despite challenges, weir fishing continues to be practiced around the largest Bay of Fundy Islands (Grand Manan, Campobello and Deer Island), defying predictions over 40 years ago that it was about to die out. The herring may not come in the same numbers as they used to, but older weirs continue to be maintained and a few new weirs are being built in the hopes of big herring catches. With the price of lobster bait (the main market for the weir catches these days) so high, it seems worth the risk to some. Weir fishing is always a bit of a gamble, as all the costs are up front and the work to set up weirs is followed by weeks and months of waiting and hoping that the notoriously unpredictable herring will come. The herring weirs that I was going to photograph are made from 40-70 foot long stakes pounded into the ocean floor, top poles (thinner, lighter birch or aspen poles around 12- 18 feet tall) and are hung with twine nets. When herring come in to the coastal areas in their huge shoals (at times, reportedly up to 9 miles long!), they are directed, by a fence attached to the shore, into the wier where they are trapped. Although all weirs follow the same principle, each is unique, its shape dictated by the currents and counter-currents, the type of sea bottom (sand or rock) and whether or not it has an additional pen for holding herring. After reading so much about the weirs and the weir fishing cultures - some favourites include Joan Marshall’s Tides of Change on Grand Manan Island Alison Deming’s A Woven World, Eric Allaby’s Grand Manan and Gwendolyn and Wayland Drew’s Brown’s Weir - I was excited to set out on my journey. Locating information on working weirs had been difficult. My scouting map was made up of nothing but educated guesses but I was going to New Brunswick with a list of names of people on the islands who might be able to help me.

Just one of the piles of fascinating books on Grand Manan, weir fishing and the Bay of Fundy

Day 1: Toronto to Saint John to Grand Manan

I started the first day of the trip with a 3:45am alarm for an early flight to Saint John, New Brunswick. The flight – only 1 hour 20 minutes in the air – was easy, as was the drive to the ferry at Blacks Harbour and the one-and-a-half-hour ferry ride to Grand Manan. I met a Grand Mananer on the ferry (82-years old and only semi-retired). I really enjoyed chatting to him and hearing, for the first time, that Grand Manan accent. Grand Manan was first settled in the late 18th century by Loyalists who left or were exiled from the fledgling American republic. The local Passamaquoddy Indians had used Grand Manan for eons as a summer fishing ground, but there is no evidence that they had set up permanent residence here. Today around 2,600 people live on Grand Manan and nearly 90% of them can trace their ancestry on the island back three generations or more (the fellow on the ferry being one of them). Weir fishing was first documented on Grand Manan in 1797, soon after its first settlement. In the late 19th century, Grand Manan was the sardine capital of the world and a century ago there were nearly 100 weirs around the island. As recently as 1986 there were 70 active weirs according to Joan Marshall. This year, though, there are just ten that have been dressed for fishing for the season. It was exciting to have my impromptu guide on the ferry point out and name the weirs I’d been looking forward to seeing for so long. I did some shooting that first evening, as it was the only day on the island where clouds were predicted.

My plane at Saint John airport in New Brunswick. I love a small airport!

The ferry from Grand Manan arriving in Blacks Harbour

Swallowtail Lighthouse, closed for long-overdue repairs

First evening. Photographing the Cora Belle weir from the entrance to Swallowtail Lighthouse. The weir in the distance is the Iron Lady.

Day 2: Grand Manan

My first full day on the island was a blue-sky day, so I took the opportunity to do some scouting. I started out the day with two short hikes trying to see if I could get some better angles on two of the weirs that are strung with twine and ready for herring. Though blue skies were predicted for all five days I was staying on the island, I wanted to know where the best sites were so I could be ready for dawn or dusk shoots and maybe an overcast evening if one came along. After the hikes I came back to the Compass Rose, where I was staying, for a well-earned breakfast.

Morning hike to Hole-in-the-Wall

Swallowtail from the Net Point Trail

Hiking along Net Point Trail

View from my room

Breakfast view

Later that first morning I met up with Alison Deming, the author of A Woven World: On Fashion, Fishermen and the Sardine Dress, a book in part about fishing weirs on Grand Manan. It was a thrill to meet her, as I had so enjoyed her book. Alison has been visiting the island every summer since the 50s and knows it, and the weirs, very well. We talked about the lack of herring so far this year and the fact that the Bay of Fundy is warming at such an alarming rate. Though there’s no definitive answer as to why the herring are not coming in the numbers they used to, she said it’s surely not because of over fishing from weirs. “It’s very hard to over fish with a passive fishery like weir fishing,” she told me. A friend of hers, Susan Price, stopped by our table as we were chatting. She told me to come to her property to photograph any time as she has a nice view of the Cora Belle weir (yes, all weirs have names). Alison also let me know that that afternoon was the opening reception for Peter Cunningham’s new photo exhibition. I have seen and admired his Grand Manan images online and was excited to have the chance to meet him, so I headed to the Grand Manan Art Gallery that afternoon. Peter was wonderfully friendly, had some good advice for me and liked the sound of my project. I really enjoyed seeing his wonderful images of the people and landscapes of Grand Manan, which he has been photographing for decades. The rest of the day I spent visiting the spots I’d put on my scouting map. Given how hard it was to nail down the locations of the weirs, I was glad to have a day to ‘ground truth’ (as archaeologists would say) my guesses about where the weirs are and to find good spots to photograph them. The day ended at Pettes Cove, as I took up the offer to shoot the Cora Belle from high ground at Susan’s home and to chat to her after the sun went down. The moonrise over the weir was magical.

Moonrise over the Cora Belle weir

Day 3: Grand Manan

The next morning, I set the alarm for 5:30am to get out for some softer early-morning light. I decided to head to the west side of the island – to Dark Harbour - to photograph the Sea Dream weir. Dark Harbour was busy at dawn when I got there, as the dulsers had been out since 3am. Dulse is a kind of seaweed that is collected at low tide around the island and the best dulse is said to come from Dark Harbour. When I got there, just before sunrise, they were mostly finishing up, as the tide was coming back in. There is a natural stone bar at the front of the harbour, so I was hoping that one of the dulsers could give me a ride over in their dory (the walk would probably take 40 minutes and the light would be over the cliffs by then), but everyone was heading home. I chatted to a couple and they said they thought I could drive in my little SUV around the edge of the harbour along a rocky road, so I tried it. I had to ford a stream, but my little rental did just fine. I walked up on the rocks of the bar and then made my way across wet and mossy stones to photograph the Sea Dream weir. There were some dicey moments and I lost a tripod foot, but it was all in service of what I hope will be a decent image. It was all a bit rushed, as I was racing the light and the incoming tide because didn’t I want to get stranded. After I got a few images, it was a matter of the scramble back up to the car and the dodgy drive over the rocky road, hoping I wasn't going to puncture a tire. I chatted to some dulsers as I was leaving and they said that the dulse they’d collected that morning wasn't as good as they hoped. The best dulse is dark, but this was 'a bit grey' one of them said. "Do you eat it?" I asked, and he replied "Some do. Crazy ones. I just sell it and turn the cash into steaks".

Dulsers coming back with their harvest as dawn breaks.

Dulser in front of the Sea Dream weir, ready to pull his dory over the sea wall.

Breakfast (egg soufflé) after my outing at Dark Harbour.

Breakfast view on a still morning. That’s a pile driver on the left. Its 800-pound maul is used to pound weir stakes into the sea floor. They are, of course, used for building new weirs but every year, after fall and winter storms, repairs need to be made on the weirs and that sometimes that involves pounding new stakes.

Dulser dories at Dark Harbour for the afternoon low tide

Dulsers going across Dark Harbour pond to the sea wall

Dulse

I got back to the hotel in time for a well-earned breakfast. The rest of the morning, I scouted a few more spots and then in the early afternoon I met up with a retired weir fisherman - Bradley Small - whom I’d connected with through Susan. Bradley’s father had bought a stake in the Cora Belle weir (the oldest weir in North Head, which was built in the 1930s) in the late sixties and Bradley been fishing it his whole life. Bradley’s son just took over his stake in the Cora Belle. The skills of and passion for weir fishing are passed down from father to son through the generations. In her book, Alison Deming describes watching a weir being seined by three generations of a family and she told me about a weir in the southern part of the island that’s been fished by the same family for over one hundred years. I really enjoyed talking to Bradley. He missed his days of fishing, saying that weir fishing wasn’t work to him, it was just fun. Families would go out to build or seine a weir and there would be hired hands to help and to take the scales (which used to be used in nail polish to give it shimmer). There were the people in the smoke houses or canneries (none exist on the island anymore) who were all part of the weir fishery. He said young and old worked together and the money flowed out to people all over the island. Now, the herring don’t come as much – probably because the Bay of Fundy is getting too warm for the herrings’ prey, zooplankton – and there are only a few weirs set up to catch herring this year. I mentioned that I’d been out at Dark Harbour that morning watching the dulsers and he said, “If you want to try some, I’ll get you some dulse”. We walked over to his neighbour’s land, where he'd laid out his dulse to dry in the sun and Bradley grabbed me some! What does it taste like? It tastes like the sea.

I spend the evening walking along Net Point Trail photographing a few weirs in the softer evening light. It had been a full and a fascinating day on Grand Manan.

Mmm… French Toast breakfast!

Day 4: Grand Manan

The next day started, again, with an alarm at 5:30am. I hoped to photograph two weirs before the sun got too high, so I headed out just before dawn. One site was easy – drive up to a lookout and shoot. The second involved a bit of a hike down to a spot above Jubilee weir to photograph it. As I got to the bottom of the trail I heard a hoarse breath and thought, “Someone is here”. I looked around. Nothing. Then I heard it again. “This time is sounds like whoever it is, they have a terrible sinus infection,” I thought. That’s when I saw the four seals playing around at the entrance to the weir. Seals are not popular around here as they are smart enough to get in and out of the weirs, eat the herring and even chase them out. I enjoyed their company, though, on my shoot. After my early-morning outing, I was rewarded with a wonderful french toast breakfast at the Compass Rose.

Before I got to the island, I had seen the work of tintype photographer John DiMartino. He has been photographing on the island, in Maine and on Campobello for a few years, including an extended stay in residence at Swallowtail Lighthouse on Grand Manan. I was excited to see on Instagram that he was having an exhibition on the island. I was going to miss his official opening, but he let me know he was at the Museum doing some last-minute work on the exhibition and would be happy to meet, so I headed over there. I saw the exhibition and heard about his process. What a labour of love! He has to make his own tintype plates, expose them (natural long exposures) and then process them within 15 minutes. Last year he started a project photographing people on the island, a series of what was known in the 19th century as ‘occupation tintypes’. To see his tintypes – each a one-off and unique piece – was a real treat, but it was also great to hear about his process and his projects. He was encouraging of my work and even gave me some locations of weirs to visit on Campobello Island, where I would be heading next.

It was exciting to see this exhibit at the Grand Manan Museum and to meet the photographer, John DiMartino. His work is gorgeous.

Model of a weir at the Grand Manan Museum

Map of all the weirs that used to exist around Grand Manan Island.

After lunch I hiked down to Pat’s Cove just to see it. The Pat’s Cove weir has been fished by the same family for over a hundred years and is located at the far southern tip of the island. The light wasn’t great, but I wanted to hike to as many weirs as I could on this visit, knowing that will prepare me for a return visit some day.

Pat’s Cove Weir. This weir has been fished by the same family for over 100 years.

Gorgeous evening at Swallowtail Lighthouse. That’s the Cora Belle in the foreground and you can see the Grand Manan Adventure ferry arriving on the island in the background.

Swallowtail Lighthouse had been closed for renovations for a few weeks, and the path to it has been closed, too. I really wanted to photograph the two weirs in Pettes Cove (the Cora Belle and the Intruder) from the cliffs near Swallowtail Lighthouse, so I asked around about getting permission. A couple of people put me in contact with the light keeper and I got permission to photograph there on my last evening, as long as I stayed away from the lighthouse. As I was setting up a shot on the bridge to the lighthouse, two of the fellows who are living at the lighthouse and doing the repairs appeared on the steps above me. “Are you the photographer taking pictures of the weirs?” they asked. I was pleased they knew I was there just in case I tumbled off a cliff - at least someone would know what had happened to me! The views were fantastic, especially down over the beautiful Intruder weir. I hope one of those images makes to the final cut.

Lovely evening

My stay on Grand Manan, despite the mostly blue-sky weather, had been wonderful. I hiked to and shot a whole lot of weirs and met so many wonderful, interesting and interested people. No one hesitated to offer their help in finding weirs, giving me names of long-disused weirs that were now only stakes in the harbour, answering my questions about weir fishing and just making me feel very welcome on the island. I really hope to make a return visit some day.

Day 5: Grand Manan – Deer Island – Campobello Island

This was the day of three ferries. I took the first ferry from Grand Manan to the mainland, then scouted some weirs and a lighthouse on the mainland before taking the next ferry from L’Etete to Deer Island. After scouting Deer Island, I took the third ferry to my final destination - Campobello Island.

The first of three ferries on “The Three Ferry Day”. This one - the largest - was from Grand Manan to the mainland (Blacks Harbour).

Green’s Point Lighthouse on the mainland.

Second ferry. This one is from the mainland (L’Etete) to Deer Island

The third, and smallest ferry from Deer Island to Campobello Island. No dock or landing, just drive down the beach and onto the ferry that someone said looked more like a landing craft than a commercial ferry.

While I was on the ferry from Grand Manan, I reached out to my contacts on Deer Island and the mainland but not surprisingly, given the season, they were busy. One of them said, “I can set you up with my mom and dad. They’d be happy to talk to you and maybe take you out to see some weirs”. I jumped at the chance and that’s how I ended up scouting Deer Island – first in talking to and then in driving around with Jane and Gary Conley. Gary is a retired weir fisherman and was a font of knowledge about the herring fishery and fishing weirs. Since Campobello Island (my next stop) had been the hardest to scout online, I asked him to help me identify the locations of weirs on my scouting map. He would point to a spot on the map on my phone and I’d mark it, either on Deer Island or on Campobello. “I don’t know Campobello weirs very well,” he said, but when I got over here, and drove around the first afternoon, the weirs were within 100 metres of where he’d told me to mark them on the map. He told me about the weirs he had built with others (his father and his brother-in-law) over the years and when we drove around, he pointed to one of them that was just bare stakes now. His son and his cousin are now weir fishermen and they have rebuilt an old weir called The Wolf off an outlying group of islands called The Wolves. When Jane talked about the two of them rebuilding a weir that hadn’t been built in over 12 years she said that the two of them – who are in their 40s – were like kids at the prospect. “It’s wonderful,” she said, “they are living their dreams” as weir fishermen. I spent a wonderful afternoon with them before heading off to Campobello.

Gary showed me an old (1932) map of all the weirs in Bay of Fundy. What an amazing piece of history!

The third, and last, ferry of the day was from Deer Island to Campobello Island. I pulled up first in line at the ferry sign, but wondered if I was in the right place, since there was no ramp, just a beach. When the ferry came, it looked more like a landing craft, but we all got on fine driving over the stone beach and on board. The ferry was a bit late arriving, so I got talking to the other people waiting in line behind me. It turns out that I had inadvertently come to Campobello at the busiest time of the year: Fogfest. In my myopia, I thought it was a festival to celebrate good, foggy photography weather (of which there has been very little so far) but, no, it’s a music festival and one of the bands that was playing – Snow Crow – was in line behind me at the ferry. I was chatting to them about my project and bemoaning the blue-sky weather when one of the band members said to me, “We’ve been coming to FogFest for 10 years and there has never been a single Fogfest where we had beautiful weather every day. You’ll get your cloudy or foggy weather”. It didn’t look like it that day, but he turned out to be right!

I spent the afternoon and evening scouting and shooting near sunset around the island. What a beautiful place! And the weirs! Gorgeous. I ended the day photographing one of the two weirs in Herring Cove. I had been to Campobello Island nine years before and had taken a picture at Herring Cove for another photo project. As I walked up on the beach and saw the weir, I thought, “How could I have missed this gorgeous structure nine years ago? Why in the world didn’t I shoot this??” There was another photographer down on the beach – shooting with a Deardorff film camera – and I got talking to him. I told him the story and he said, “No wonder you didn’t notice it - it wasn’t here nine years ago. This weir was only built two or three years ago”. In fact, a number of new weirs have been built around Campobello since 2020. Though there are so many fewer weirs than there used to be, it’s a joy to hear about new ones being built.

Breakfast at The Porch on Campobello Island.

Day 6: Campobello Island

One my first full day on Campobello Island I was out early to photograph before sunrise. The weirs on Campobello Island were a joy because even though there are only six or seven weirs that I could see from land, many of them are accessible along a beach. In Grand Manan I could see weirs on a hiking trail through a single break in the trees, which meant there really was only one shot to be made. Photographing on Campobello was more fun because I could get relatively close to the weirs and try different compositions.

After my morning shoot and a hearty breakfast (the theme of the trip, it seems) I did some scouting of sites around the island then crossed over to the US (Maine) to visit a lighthouse and buy some chocolate. When I was in Lubec, Maine nine years ago, I visited a fantastic chocolate shop and lo and behold, it was still there. I wanted to get a gift for my friends on Deer Island and what could be better than fancy handmade chocolates?

Mulholland Point Lightouse, Campobello Island

East Quoddy Lighthouse, Maine

That evening was a lovely one: I visited two weirs and because of some high clouds and soft light, I didn’t feel as rushed to get images in a short time; I could take my time to enjoy the sound of the waves and wander around looking for good compositions.

Day 7: Campobello Island

The day started with another early morning shoot, trying to catch the soft morning light. The islands I visited are at the head of the Bay of Fundy, which has the highest tides in the world. Farther up the Bay, the tides can get above 13 metres (over 40 feet). Where I was they were a respectable 7.1 metres (23 feet). In addition to trying to get soft light I was also trying to photograph weirs (and lighthouses) at different tides. The complete structure of the weirs are obviously most visible at low tides, but they have a certain fragile elegance at high tide when only their top poles can be seen above the water.

Head Harbour Lightstation at dawn, near low tide.

Head House Lightstation, near high tide.

Since Fogfest was in full swing, I thought I’d go to one of the concerts (I had my eye on the Snow Crow concert – the band I met on the ferry from the mainland), but then the clouds rolled in and I was off! What luck that the weather changed at the end of my time on Campobello – the island that I had had days to scout and which has seven weirs visible from shore. I drove by the The Porch, where Snow Crow was playing and saw there was a line of cars parked along the road. That made me happy – I knew they had a packed house and wouldn’t miss one photographer not being in the audience. I spent the afternoon visiting all the weirs I’d scouted and ended up at Herring Cove which has two great weirs accessible from shore. It was also the main outdoor venue for the festival, so I was photographing to the sound of the bands playing that night.

Clouds rolled in over Herring Cove, Campobello Island.

Fogfest in full swing!

Day 8: Campobello - Deer Island

Early forecasts had shown some possibility of fog on Saturday morning and when I saw that I decided to stay an extra night on Campobello. That decision had already paid off with clouds the night before but then I woke at my usual early hour to a little fog. That little bit of fog was enough to catapult me out of bed to an amazing morning of photography. Originally I thought I would take the 8am ferry to Deer Island, but the fog settled in so I missed it and the 9am ferry, then the fog lifted a bit, so I thought I might make the 10am ferry, but then the fog returned, so I missed that ferry, too. I wanted to get as much out of the amazing conditions as I could!

Foggy Herring Cove

More beautiful foggy conditions.

At one stop, as I was photographing a weir, the owner of the property stepped out of his house to chat. A couple of days before I had knocked on his door to ask if I could photograph the weir from his front lawn and he had been fine with it. He didn’t own the weir that I was shooting but when I said how beautiful I thought they were, he said, “They’re quite the contraption, aren’t they?” Quite the beautiful contraption, indeed.

Ferry to Deer Island arriving on that foggy morning

Foggy crossing

Goodbye to Campobello Island

I really wanted to photograph the one weir easily visible from shore on Deer Island – the Piggen – not too far off low tide (which was 9:30 that morning), so I made the decision to catch the 11am ferry. It was a beautiful, mysterious, foggy sail across to Deer Island, where I managed to photograph the Piggen just as the fog was lifting. As I was taking my last few shots, I got a call from Gary – the retired weir fisherman whom I’d met on my way through Deer Island a few days before. We had tentatively planned to go out in his boat at low water that evening, but he and his wife had been invited out. “Do you want to go now?” he asked. “Sure!” was my response. I packed up my gear and rushed over to their place, as we were losing the tide and he, his wife Jane and I went out to see some of the weirs around Deer Island. What a treat it was to be taken out like that and to see the weirs up close – we even went inside a couple of them. The tide was rising so they weren’t completely visible, but at high water they are still beautiful. When we got back to the wharf, we ran into Dale, his wife Lois and two of their grandchildren, arriving in their boat. Dale is Jane’s brother, a well-known weir fisherman on Deer Island who had already offered to take me out to his weir – the Abnaki – and others around the island. Dale’s family has been weir fishing since the early 19th century and I was eager to talk to him about the weirs. He offered to take me out in the evening, closer to low tide, when I’d have a completely different view of the weirs.

Weirs get damaged regularly and mending weir nets is a bit of an art. This mend is done so beautifully.

Each knot on the hundreds of metres of netting has to be tied by hand

At this point it was 3pm and I hadn’t eaten anything but a protein bar for breakfast, so I went along to the Ocean View Takeout to have fish and chips on the deck overlooking the ocean. Before I met up with Dale for our evening sail, I checked into my B&B, which happens to be owned by the owners of Mercury Ice Cream on Deer Island. When I booked it over the phone in March, I was told that my room came with ice cream, if I wanted it, every day. I was sold! I had my ice cream on the porch overlooking the ocen, before I rushed off to meet Dale.

View from the Ocean View Takeout

Mmm… delicious fish and chips!

Ice cream on the porch

We visited the same weirs that I’d seen that afternoon, but what a difference! We would arrive at a weir, I would look up over 20 feet above me to the high water mark and think, “I was up there this afternoon”. Dale had some fantastic stories to tell and his passion for weir fishing was obvious. He talked about how he learned to fish from his father, how his father ‘sort of retired’ at 77, but kept helping out in the boats right into his 80s. I’m sure Dale will do the same. There are so many things I remember about this wonderful evening, aside from seeing the weirs, including Dale rhyming off the names of a dozen weirs that have now disappeared which were located where the farmed salmon pens now stand. As we approached his weir - the Abnaki - he turned off the engine and set to rowing us in. Every day (often twice a day) he will come out to the weir to check if there are herring in it. “We have to row in,” he said, “the motor will scare the herring”. We rowed around inside the weir - a beautiful quiet evening with nothing but the sound of the waves and the click of the oars - but there were no herring. This check is now done with sonar, but in the past fishermen used to ‘feel in’ by dragging a weighted copper wire through the water to feel if there were herring were inside the weir. Some fishermen - Dale said Gary used to be very good at this - could tell with great accuracy how many hogshead (a measurement) of fish were in the weir just from the bumps felt on the wire. “I love this part, checking the weir,” Dale said, proudly showing me how worn the oars were from his frequent visits; he has to get new oars every season.

We got back to shore around sunset, I headed back to my place and I collapsed into bed after an absolutely wonderful day and slept like a log.

Evening visit to weirs around Deer Island

Dale Mitchell rowing us into Abnaki weir

Going into a weir - this is where the herring would enter if there had been any

Day 9: Deer Island

The next day was another blue-sky day, but after going so hard for a week - sleeping no more than 6 or 7 hours a night - it was nice to have some time to relax. After a morning sitting on the porch reading, though, I needed to get moving. I guess I’m not very good at relaxing on my vacation!

I headed down to the southern end of the island to see the The Old Sow. The Old Sow is the largest tidal whirlpool in the Western Hemisphere. I guess it’s not surprising that it would be located here, in the Bay of Fundy, which has the highest tides in the world. Dale told me on our trip out to the weirs that more water moves through the Bay of Fundy than all the rivers in the world. Actually during one twelve-hour tidal cycle, twice as much water moves through the Bay of Fundy as moves through all the rivers in the world in the same time period. It really beggars belief, but when you see the same spot at low and high tide or see (and hear) the The Old Sow moving water near to high tide, you can begin to believe it.

I puttered around the rest of the day, until late evening, when I went out to shoot. I headed up to the Piggen weir, my favourite on the island. There I met two women out walking their dog. They were just visiting the island, but one of them had grown up here. She said, “From that house up there, in the 60s, you used to be able to see seven weirs. Now you can only see one”. Then she pointed to the other side of the cove, “My father’s weir used to be there. That was a good weir. That weir put me through university”.

Day 10: Deer Island

My last full day on Deer island started out again with – you guessed it – blue skies and I started off my day with a leisurely morning on the porch, including a breakfast of fresh made pastries!

Fresh-made pastries for breakfast

The day’s ice cream flavour.

Most of the day was bright and sunny and things were closed down for New Brunswick Day, so I sat on the porch and read. At low tide I went out to shoot some weirs but, really, the light was just too harsh. The clouds rolled in, however, around 6pm and I got a final evening’s shoot of the weirs around Deer Island. A lovely goodbye to the island I had enjoyed so much.

Early morning ferry ride.

Day 11: Deer Island – Saint John – Toronto

I woke up at 4:45am on my last day to catch the first ferry to the mainland. I didn’t need to leave so early, but I wanted to shoot the Green’s Point Lighthouse on the mainland, which I’d seen on the way down a few days earlier. The ferry ride was the sixth of this trip! I shot the lighthouse and had breakfast in Saint John, then headed to the airport.

I had been thinking about and planning this trip for over a year and had some pretty high hopes. In terms of the welcome I got, the amount that I learned and what I saw - all my hopes were exceeded. I was amazed at all the people I met who shared their knowledge and their love of this area, of fishing weirs and the fishing life. The weirs themselves were so beautiful. Alison Deming was right when she called them ‘earth art’. Despite mostly blue-sky days, shooting at dawn and dusk and getting a couple of days of good conditions meant that I am returning home with hundreds of images. Thank you to everyone I met or spoke to from Grand Manan, Campobello and Deer Island. Your generosity made the trip a very special one.

If you’d like to comment, please feel free to leave one below. You don’t need to make an account, just enter a name and click ‘comment as guest’.